The Unibiquitous Rebirth of Cool. In a world where authenticity became common, what is inimitable became copious, influencers became branders, until the novelty wears off.

It wasn’t easy, no 1, 2, 3

Took a long time to learn to feel free

But here I am Vogueing pretty

In some club deep in this city

Deep In Vogue ~ Malcolm McLaren

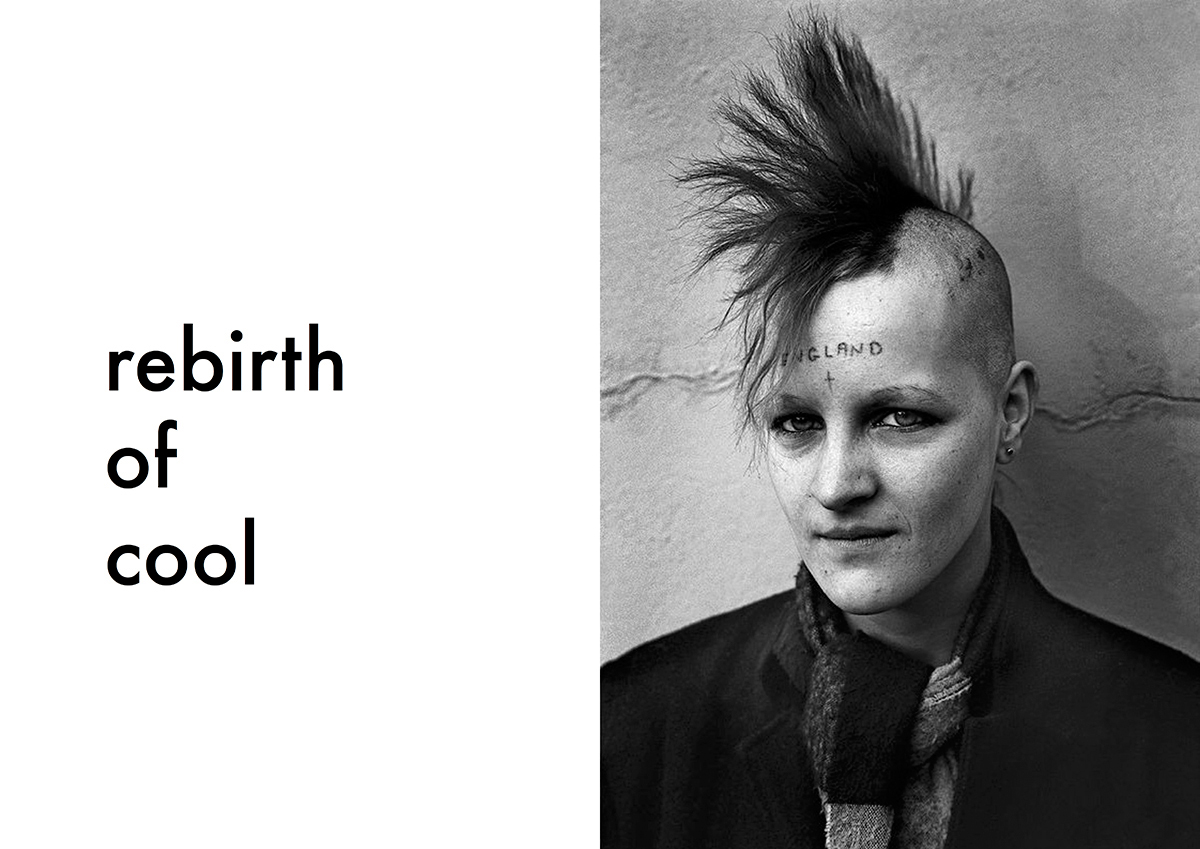

First, let me say this: when I think about street-style, I think about real originality, real rebellion against what is dictated by the current trend. It is about dressing up for no one other than yourself, carrying your own brand of vogue with pride. It is about being crafty and ingenious, by exhibiting a clash of materials and forms and patterns and colours in a way that enables you to get your message out to by-standers and random strangers. It is about exploiting fashion to further articulate things that matter to you most and renouncing those that don’t, proudly proclaiming what is noble and what is evil in your personal bible.

Street-style, it seems, is the lovechild of clashes in socio-economic and cultural paradigms. It is a great reflection of the complexities mostly prevalent in many urban megalopolis, stemming from the grassroots and youth culture. While it has been around for many years, only in the last few decades had the term street-style been so widely fêted.

As anthropologist Ted Polhemus once said in his book “Street Style”, “arguably the most profound and distinctive development of the twentieth century was this era’s shift from high culture into popular culture-the slow but steady recognition that innovation in matters of art, music, and dress can derive from all social strata rather than, as previously, only from the upper classes. As much as, for example, the twentieth century’s accreditation of jazz, blues, folk, and tango as respected musical forms, the re-evaluation of street-style as a key source of innovation in dress and appearance-in the early 2000s, a principle engine of the clothing industry-demonstrates this democratization of aesthetics and culture.”

During the latter half of last century, the world’s socio-economic ladder has turned the greater mass to adopt fashion trends that are not only intellectually fierce, they are also provocative and subversive. In many fashion history literatures, scholars and enthusiasts would reflexively group these grassroots fashion movements into style “factions” – for example: Soda-pop, Teddy Boys, and Greases of the 1950s; Mods and Hippies of the 1960s; Punks, Disco, and Glamrocks of the 1970’s, or the Ravers, Hip-hoppers and New Wavers of the 1980’s.

While for the first time in modern history, the youth became the leaders of fashion with these new and radically innovative street-styles, Polhemus noted that during these periods “the high-fashion world remained largely impervious to influences from outside the tight sphere of elite designers and their wealthy customers, a broader perspective on dress reveals a growing appreciation of styles and fabrics with distinct, explicit working or lower-class roots and connotations.” Each “style faction” lingered en masse only as the high-end’s “alternative”, as an anarchical fashion movement within the middle and lower social strata. The youth pledging alliance to each faction follows the trend decreed by their sub-culture clique, while runway and high-end fashion are still represented by the voices of the perfectly poised.

It is only thanks to the unprecedented appeal of impromptu sidewalk photographs by Bill Cunningham and the publication of magazines such as i-D and FRUiTS in between the 1970’s to the 2000’s, the elites of fashion world has closely acknowledged the importance of urban youth culture. Those on top of the fashion food-chain conceded to scrapbooking candid snaps of regular people on the street to score raw, bold, edgy, matter-of-fact sartorial inspirations.

Those growing up in the turn of the century adopt modern variations of their predecessor “style factions”, only this time, each person dictates his/her own sub-culture. This new generation of youth contextualize their uniqueness immediately without having to kowtow to the style adopted by their peers. Contrary to the editorial leitmotif found in high-end fashion magazines, in street-style publications you can find snapshots of a goth girl sporting a mod hairstyle, a b-ball rapper with a cowboy hat, and a punk-rock Cinderella – all in the same page.

The irony, however, still remains. Because of the immense randomness and the high turnover of surprise elements in this new wave of sub-culture, fashion moguls realized that the only way to keep in touch with their customer base is by paying tribute to this phenomenon. How? Of course by commodifying these people on the street as aspirational tastemakers, letting them sit on the throne usually reserved for celebrities and iconic models. This create an illusion that everyone and anyone can dictate what’s hot, allowing price points and marketing forecasts to become tremendously volatile. The result? Paying couture prices for a pair of tracksuit and Ikea-inspired tote bags have become the new normal.

As we enter the Internet era, blogs and Instagram replace traditional publications, and the millenials understand that they can monetise their self-expressions. They no longer need industry gatekeepers and fashion magazines to approve their marketability, they become their own brand manager. The role of editors has since diminished, and the gentrification of street-style led to the closure of even the most organic sub-culture fashion bibles like The Face and FRUiTS. The for-profit fashion industry milked in on this globally newfound vulnerability – showering these instant celebrities with praise, endorsed goods, and money – until what is authentic became common, what is inimitable became copious, influencers became branders, until the novelty wears off.

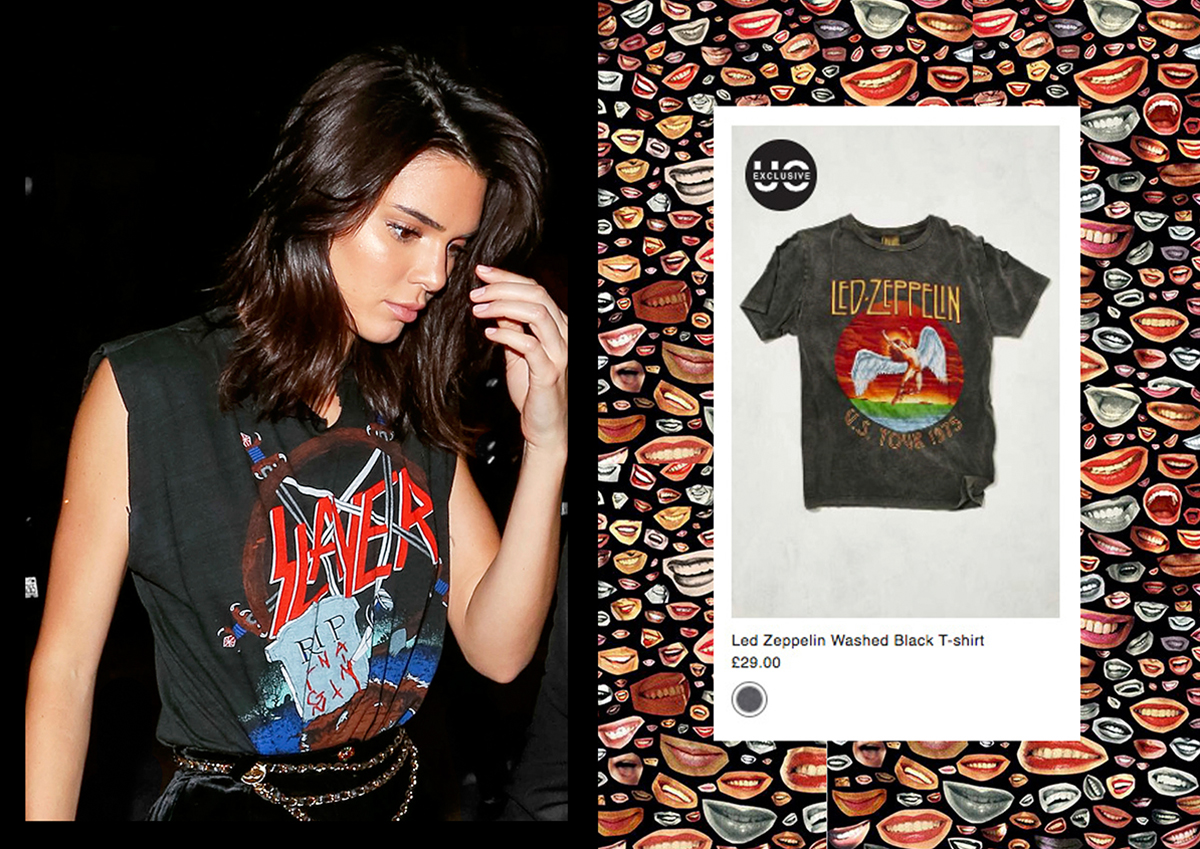

Is it still street-style, when the ultimate goal of attending fashion week is “peacocking” in front of photographers in your most elaborate ensemble, hoping to be propelled into fame by the next Scott Schuman and cashing in one’s efforts? Is it still street-style, when you have the same eyebrow shape and lip filler as any of the twenty girls next to you, wearing metal band t-shirts without even knowing a single album released by these rock gods? Yes, those blog posts or Instagram pictures are taken on the street, but is it still street-style, when those photographs became a blatant competition of girls pretending to be candidly nonchalant but in reality looked too framed up, clad in endorsed goods and metamorphosed as brand billboards?

To quote Kim Harstreiter, the editor of Paper magazine, “Great street-style comes from within, not from outside forces like globalization. It cannot be “manufactured” because of its very nature – it is unique, customized and in no way about conformity. The best of which, to me, communicates personal identity through ideas and never through fashion, trends or status. Great style is as unique as the person, reflecting who they are, how they live and what they believe in. The most innovative street-style tends to be created in the absence of wealth, rarely from wearing fashion labels bought off racks.”

In a world where keeping up with technology is harder than keeping up with the Kardashians, we can only hope that in the future, creativity and personal expression will still outweigh staged collaborations and numbers of likes. Personal style should always be about “this-is-me” and less about “look-at-me”. It’s never as easy as 1, 2, 3, but we should not let the fire of authenticity to be extinguished so easily. Recite this mantra: Vogueing pretty is wearing our hearts on our sleeves (and shoes and dresses and pants and jackets and makeup), ever so proudly. (Text Winda Malika Siregar)

CREDITS

Graphic design and layout Rahajeng Puspitasari